While a painting like ‘The Origin of the World’ may still strike us as unusual or extraordinary, representations of the vulva are actually quite common in some of the oldest archaeological evidence of human cultural activity. These records provide insight into a time in human history when female genitalia were not concealed, but instead were regarded as sacred. Paleolithic cave paintings, such as those found in the caves of Lascaux or La Ferrassie in France, depict numerous representations of the vulva. Throughout the Neolithic to classical antiquity, female figurines featuring exposed vulvas played a significant role in ceremonies, festivals, and various rituals. Of particular interest are certain figurines that have been uncovered in Greece and Turkey, including some found amidst the ruins of the Eleusis sanctuary, which was widely regarded as the foremost religious center in the ancient world. This site was the setting for the famous «mysteries,» a set of initiation rites that lasted for more than two thousand years, from archaic times to the last gasps of the Western Roman Empire.

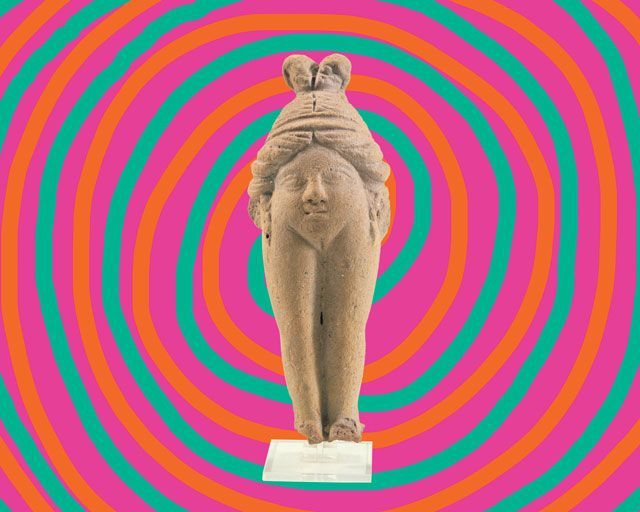

The figurines depict a woman lifting their skirts or represent her directly as vulva-women. What makes these figures particularly intriguing is the presence of the woman’s face on the belly, with a smiling expression and a chin groove that mirrors the vulvar slit and crotch. This unconventional representation confuses the traditional boundaries between the upper and lower parts of the body, as if the figure had turned herself inside out.

These statuettes have been identified as representations of Baubo or Iambe, a mythical old woman who boldly lifted her skirt and display her vulva in front of the goddess Demeter, without any sense of shame. Baubo/Iambe gained notoriety for her brief but significant role in a captivating Greco-Roman myth: the tale of the abduction of Persephone-Kore by Hades and the desperate search of her mother Demeter. It is worth noting that both goddesses are associated with the earth and agriculture, vegetation, and fertility, particularly of crops such as wheat (hence Demeter’s Latin name, Ceres). Hades, the abductor, is also associated with the subterranean realm, commonly referred to as the underworld, which is regarded as the lower state of the world or the «womb» of Mother Earth. Is this the realm of death? Yes, indeed. However, this space did not carry the same moral weight of condemnation that was later imposed on the Christian concept of infernus (a Latin term originally referred to an inferior region rather than a place of eternal damnation). In the myth of Demeter, Persephone, and Hades, death is closely linked to the earth, which generates all things and then reclaims them in a constant cycle of death and renewal. This cyclical nature of life and death is reflected in the story of Persephone’s abduction and eventual return from the underworld

To begin the story, we must first ascend to the heights of Mount Olympus, where the gods of ancient Greece ruled from their divine abode. Much like the world’s current leaders, who make decisions from the comfort of their offices in towering skyscrapers, in ancient times, Father Zeus, reigning from his throne in the clouds, held the power to determine the destinies of both mortals and immortals. On this occasion, he had decided to give his daughter Kore to his brother Hades to be his wife. Of course, neither Kore nor her mother Demeter had been consulted or informed of this decision. The myth presents Kore living up to her name, which means «girl,» «young maiden,» or «virgin,» as a free-spirited young woman without any attachment to a man. We see her running through hills and forests, carelessly picking flowers with her friends, the daughters of the god Oceanus. In a cunning move, Hades entices his young prey with a beautiful and radiant narcissus, like a skilled hunter luring their target. As soon as the girl takes the bait, the god emerges from the depths of the earth, riding his chariot, and forcibly takes Kore to the underworld. In Graeco-Roman mythology, it’s not uncommon to find stories of gods committing heinous acts by violating women and goddesses, with many of these acts going unpunished. The abduction of Kore by Hades, however, is a notable exception to this trend.

Distressed by the disappearance of her daughter and the complete indifference of the gods, Demeter decides to leave Mount Olympus. And so, while her daughter pales with grief in the underworld, the inconsolable mother takes on the form of an old ragged woman and sets out to roam the lands of humans in fruitless search for her daughter, without stopping to drink or eat anything. Everything appeared to be unfolding as Zeus and Hades had intended, but they could not have foreseen the calamitous consequences of the harvest goddess’s profound affliction. If Demeter, the goddess who oversees the fertility of the earth, were to fall into despair and lose her vitality, the entire world would inevitably be plunged into a state of sterility and paralysis. And that’s exactly what happened. In just a matter of days, all vegetation withered and died, and nothing else would take root in the soil. The fertility of the earth was completely compromised, and even human reproduction came to a standstill. This was the harshest and most unforgiving winter the world had ever known, one that seemed as if it would never come to an end

At this crucial moment in the story, Baubo/Iambe makes her entrance. Her two names come from the divergent versions of the myth. According to the Hymn of Demeter, attributed to Homer, Iambe —from whom the ancient Greek iambic or satirical poems take their name— was a servant in the palace of the kings of Eleusis. Unaware that she is a goddess, they had employed the grieving and despondent Demeter as a governess to one of their sons. Observing Demeter’s lethargy and unrelenting fasting, Iambe takes it upon herself to cheer her up. She offers her a chair to rest and food and drink, but Demeter refuses. Undeterred, Iambe decides to cheer up the goddess by telling bawdy jokes and making mocking gestures, which soon elicit laughter from Demeter, as Homer tells us.

An alternate version of the myth, derived from the Orphic texts, provides the most explicit account. No fancy palace or rulers in Eleusis in this version. Just a simple hut where a couple of peasants live and offer help to the goddess as best they can. The woman, referred to as Baubo —a name that in ancient Greek means «vulva»—performs an obscene dance in front of the dejected Demeter. The dance culminates with Baubo lifting her skirts and exposing her genitals, in a gesture known as ana suromai or anasyrma. This gesture provokes the uncontrollable laughter of the goddess of the harvest. Following this, Demeter’s mood changes and she readily accepts a mysterious drink called kykeon from Baubo. The recipe for kykeon is said to include barley water, mint, and other secret ingredients, and it played a crucial role in the Eleusinian mysteries. In fact, the Homeric hymn mentions that it was the goddess herself who, after revealing her identity and in gratitude to the people of Eleusis, established her temple there and instituted the famous mysteries.

By making bawdy jokes and raunchy gestures, Baubo/Iambe successfully breaks through Demeter’s sadness and triggers the end of her fast, restoring her good mood. This decisive intervention by the vulva-woman brings about Demeter’s recovery, granting her the strength to confront Zeus and rescue her daughter from the underworld.

Under Demeter’s pressure, Zeus and Hades were left with no choice but to capitulate. The myth recounts a bargain struck between the gods: for the world to flourish once again, Demeter demands the prompt return of her daughter in exchange. And so it happened. The Homeric hymn beautifully narrates the reunion of the mother with her daughter. Demeter waits eagerly in her temple at Eleusis for the arrival of Hermes, the messenger of the gods who brings back Kore. Finally, when the goddess sees them approaching, «she ran towards her daughter like a maenad running through a mountain ravine.» However, while buried in the depths of the earth, Kore had undergone a profound transformation; she was no longer the girl we encountered at the beginning of the story. She had become Persephone, the guide of the souls of the underworld.

Some have interpreted this myth as a coming-of-age journey, the representation of a rite of passage to womanhood. However, it is important to note that Persephone’s emergence as an adult woman is not a result of her violation as the young girl Kore. Such an interpretation would suggest that a woman’s transition to adulthood is dependent on subjugation to a dominating male force. Nonetheless, the myth’s message is far more intricate and meaningful.

As Persephone prepares to leave the underworld, Hades offers her the seeds of a pomegranate, one of the forbidden fruits found in myths from various cultures around the world. This act binds the young goddess to return to the underworld for one-third of the year. However, it’s possible that Persephone voluntarily ate the seeds, fully aware of the consequences. The story of Demeter and Persephone is often considered the most feminine among all classical myths. Despite the patriarchal nature of ancient Graeco-Roman societies, it was widely celebrated and esteemed, particularly by women, due to its prominent female characters. Moreover, the story contains a secret code, conveying an uplifting and practical message that was understood by women in ancient times, although it remains somewhat veiled to us today.

The irony of the story’s outcome is significant, and it lies in the pomegranate seeds. Hades believed he had forced Persephone to spend one-third of the year with him, but instead, he had unknowingly provided her with a means to safeguard her independence and freedom. The Lord of the Underworld was likely unaware that the pomegranate seeds were known to cause sterility in women. Ancient Greek and Roman medical texts frequently mention the abortifacient properties of pomegranate, among other fruits and herbs. Pomegranate seeds were widely used as a natural contraceptive in antiquity and are still utilized for this purpose in India, Africa, and Polynesia.

For women in ancient times, the obscene gesture of Baubo was a revelation that unlocked the hidden wisdom within the myth. The sacred anasyrma gesture, in which women exposed their vulvas, was performed in festivals and cults to honor Demeter and her daughter. Through this act, Baubo revealed the power of femininity and reminded Demeter of her ability to manage her fertility, either to give or take life.

From a cosmic perspective, the outcome of the myth marked the beginning of the seasons or, more precisely, the seasonality of the harvests. This is, in fact, the most superficial and well-known interpretation of the story: when Persephone is with her mother in Eleusis, the earth bursts forth with fruit, and the world enjoys spring and summer; when she descends with Hades, the earth appears barren and lifeless, signifying autumn and winter.

But what does this moral tell us except that life is in constant motion, in constant flux and change? The descents and ascents of Kore-Persephone mirror the cycles of the stars and the cycles of vegetation in their continuous process of becoming and decaying, blooming and wilting.

Curiously, certain obscene and vulgar expressions that persist in our language today still echo the sacred meaning of Baubo’s anasyrma, or the act of displaying the vulva. After all, isn’t sending someone to the nether regions the basic premise of countless obscenities? Baubo’s gesture, in fact, appears quite similar to rude expressions such as «kiss my…» or «go to…». Particularly, in Spanish swearing often involves directing someone to their mother’s vulva by using terms such as «coño,» «concha,» «chucha,» or «chocha.» Interestingly, these insults symbolically represent a return to the earth, to the origin, to the «origin of the world,» to the uterus or womb, where one must dissolve and be reborn. Like a posthumous joke from Baubo herself, these obscene expressions reflect a cycle of destruction and rebirth that mirrors the natural rhythms of life and death. Adhering to a non-binary logic, every negation is followed by a subsequent affirmation.