Prior to the writing of the Book of Genesis, which is believed to have been composed between the 10th and 6th centuries BCE, humanity knew other beginnings. Ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, now present-day Iraq, thrived long before patriarchal systems emerged. Then, the thrones of the patriarchal gods had not yet been built in the high heavens, simply because there were no thrones to eternalize on the face of the Earth, nor any armies to defend them. The oldest written records and archaeological artifacts from this region point to a more egalitarian society, where the idea of an authoritarian God-Father was unnecessary to justify a hierarchical order. Divinity was not yet gendered or characterized as a singular male figure residing above the earth. In fact, the binary opposition and unequal evaluation of male and female had yet to be established.

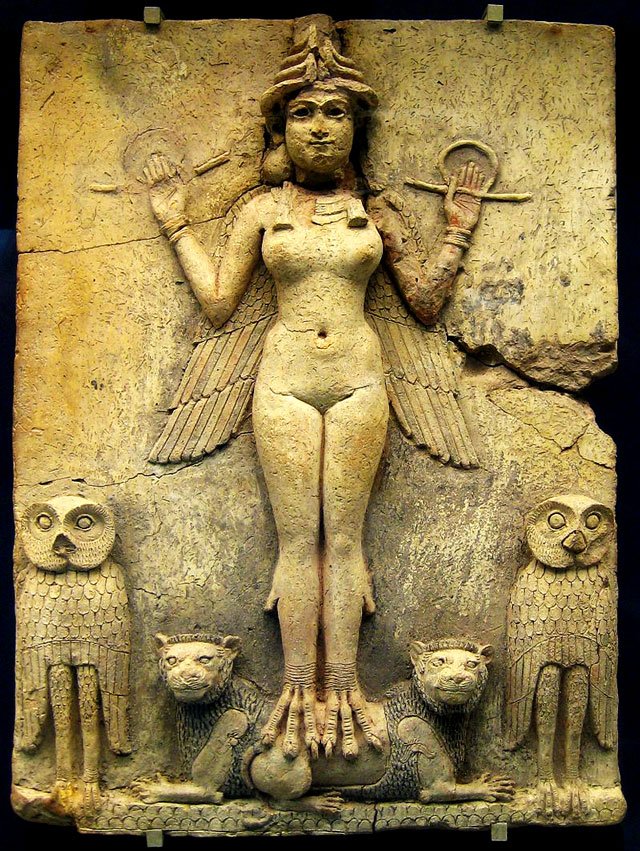

During the fourth millennium BCE, the Sumerians worshipped a deity who defied gender binaries, blurring the boundaries between male and female. This non-binary and unclassifiable deity, known as Inanna to the Sumerians and later as Ishtar to the Akkadians and Babylonians, easily erased the barriers between the opposing realms.

In the ancient Sumerian belief system, Inanna is depicted as an independent deity without marital ties, often referred to as the «Great Lady of Heaven and Earth.» Every day, Inanna would appear twice in the sky as the brightest light – once at dawn and again at dusk – in the form of Venus, the morning and evening star. Moreover, Inanna encompasses both the dark and luminous phases of the moon, embodies both the destructive and creative aspects of nature, and can be seen both high in the sky and sunk in the dark underworld. In a word, this multifaceted deity is better described as a paradox.

The Sumerians are credited with the invention of writing. In their ancient cuneiform tablets, discovered in the Persian Gulf, the paradoxical nature of Inanna becomes evident. This goddess was worshipped as the deity of fertility, motherhood, and sexual love, similar to the Greek goddess Aphrodite and the Roman goddess Venus. However, Inanna also had masculine qualities and was sometimes even referred to as the «bearded goddess.» In a Sumerian text, Inanna introduces herself with the following words:

When I sit in the ale-house, I am a woman, but verily I am an exhuberant man (…). When I sit by the door of the the tavern, verily I am a prostitute who knows the penis. The friend of a man, the girl-friend of a woman.

Inanna’s remarkable ability to traverse seemingly opposing realms with ease speaks to her versatile and fluid nature. She moves seamlessly between genders, from sky to earth, from earth to the underworld, and from divine altars to earthly taverns. Inanna’s complex persona also encompasses seemingly disparate roles, from goddess to prostitute.

Was Inanna a woman? Was Inanna a man? These questions arise from our cultural conditioning, which predisposes us to assume that everyone, including deities, must define themselves in a binary way. However, the earliest Sumerians did not show much interest in elucidating Inanna’s gender. The truth is that Inanna’s allure was irresistible, and everyone fell at their feet. It is best to assume that the supreme divinity of ancient Mesopotamia was an androgynous entity, a fusion of man (andro) and woman (gyne). This hybrid entity was capable of playing with the edges of gender, navigating sexual boundaries, and embodying both feminine and masculine traits while also being neither feminine nor masculine. Thus, Inanna embraced an ambivalent, fluid, and ultimately unfixed identity.

Encountering representations of divinity that challenge our conventional and binary understanding of gender can be unsettling. This is because our cultural model encourages binary thinking, which justifies the stark separation and hierarchization of masculinity and femininity. The androgynous offers a different perspective, which is a dazzling one that patriarchal systems struggle to digest, often rejecting it as «unnatural» or «against nature.» But we know (or should know) that nature does not limit itself to producing only the two morphological possibilities that our cultural imagination has defined as the boundaries of possible bodies. There are also intersex people who are born with reproductive anatomy or sexual characteristics—genitals, gonads, and chromosomal patterns—that combine both male and female traits at the same time. However, although intersexuality is a perfectly natural variation in human beings, it is rarely thought of in our contemporary world as anything other than an anomaly that must be corrected through mutilating or normalizing practices.

Despite this, history offers us numerous examples that demonstrate how humans have not shied away from imagining and depicting ambiguous bodies, imbuing them with a sacred essence and regarding them as the most complete expression of humanity or the most accurate image of plenitude. In particular, the myth of the androgynous origin of human beings is reiterated in various civilizations throughout history. Its presence is notable in Greco-Roman and Hebrew traditions, two of the primary sources that have shaped our Western patriarchal cultural imagination. In a similar vein, the medieval European Christian thought depicted the androgynous figure as the epitome of human perfection, even associating non-binary sex with heavenly beings such as angels and with biblical figures such as Adam and Eve, as well as with Jesus himself.

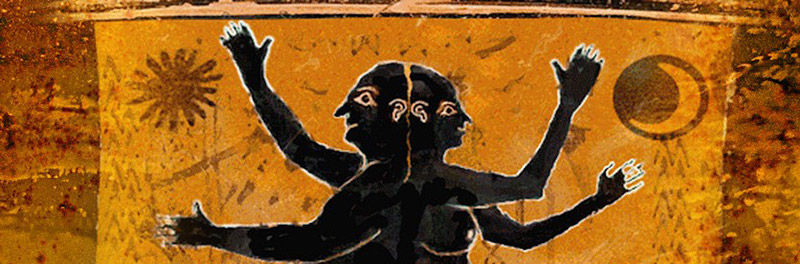

Plato’s famous dialogue The Symposium features a notable passage centered around the topic of love and its various manifestations in human life. In this exchange, the great philosopher has the brilliant comic playwright Aristophanes narrate a fascinating tale of humanity’s happy origins, in a golden age when three distinct genders coexisted as the remote ancestors of later generations. According to Aristophanes, at that time, there were male and female beings, as well as a third, enigmatic hybrid of both genders known as the androgynous. All of these beings were exceptionally vigorous and possessed a spherical body with two opposing faces, four ears, four arms, four legs, and two sets of genitalia. As such, these original beings were dual in nature: some were male-male, some were female-female, and some were male-female. Round and content, none lacked their other half, and they all lived in harmony.

Tragically, as is often the case in myths that depict an original state of wholeness or perfection, their joy was short-lived. According to legend, the first humans, who were once united as a single being, showed disrespect towards the Olympian gods. Zeus, in his wisdom, punished them by splitting them apart with a thunderbolt and thereby doubling the number of his worshippers. Aristophanes describes these doomed creatures as driven by an overwhelming desire to seek out their other half, from which they had been forcibly separated. Upon their reunion, they clung to each other with such fervent passion that they perished from starvation and inactivity, unable to do anything else but embracing their other half.

This Greek myth beautifully illustrates the origins of three sexual orientations: homosexuality, lesbianism, and heterosexuality. However, it also reveals the source of our fragmentation, which is the root of our anxieties and desires, our solitude, and our inevitable need for others, whom we sometimes cling to desperately in search of salvation. And so begins the human struggle, our endless quest to heal the wound of our separation, our constant yearning for a sense of wholeness and belonging. Zeus, in his wrath, cleaved us in two with his lightning bolt, leaving us as incomplete beings, doomed to roam the earth in search of our missing halves.

In fact, it could be said that Zeus punishes humans to feel more secure in himself, more confident in his own authority and omnipotence. By mutilating the original humanity and ending the androgynous beings, the god of lightning created needy and longing creatures who would later look up to the sky for feeling unhappy and fallen. In truth, without a fallen humanity, a god reigning in the heavens would be inconceivable. Analogous to Plato’s myth of the androgyne, the first account of the creation of Adam in the Hebrew Genesis hints at the presence of a primal androgyny in human beings. Prior to recounting the widely-known tale of Adam’s creation and the formation of Eve from his rib (Genesis 2:7, 21-25), the biblical text succinctly declares:

«So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.» (Genesis 1:27)

This passage suggests the idea of a human race that is androgynous in nature, created in the likeness and image of an equally androgynous divine entity. Elohim, one of the Hebrew names for God (or gods, as the divinity in Genesis occasionally speaks in the plural, «Let us make mankind in our image»), is derived from the combination of the singular feminine Eloh and the plural masculine im. The notion of an androgynous deity in Genesis is not unfounded, given that the text is known to be far from uniform or consistent. Quite the contrary, is a medley of tales interwoven from various cultural traditions that predate it, including the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia.

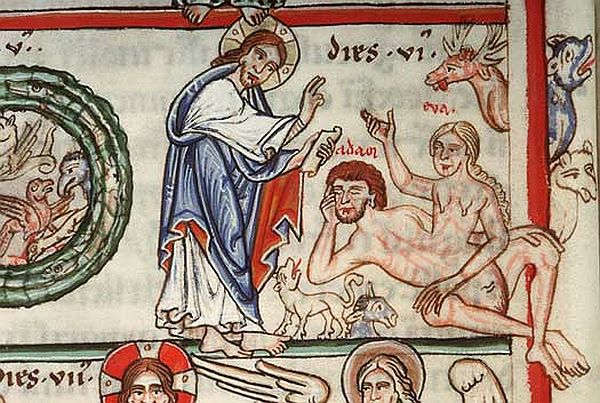

From ancient times to the Middle Ages, the notion of a non-binary figure, often referred to as «androgyne» or «hermaphrodite,» will be a constant in religious thought, driven by the desire to imagine an idyllic, pre-Fall human race. Rabbinic and Christian interpretations of Genesis 1:27 («So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them») both identify it as the depiction of the first human prototype, which would have encompassed the male and female sexes seamlessly fused into a single entity. Building on this initial reference to human creation, for example, Jewish Midrashic tradition depicted Adam as a hybrid body of both masculine and feminine forms, with two faces and two genitals. According to this view, Adam’s body, which contained the rib from which Eve would be formed, was thus composed of two sexes until Eve was extracted from him. The story of the rib in Genesis 2 would describe the separation of the primordial androgynous human into two halves, one male and the other female. In Midrash Rabbah, a collection of Midrashim on the books of Genesis and Exodus, we read:

And God said let us make a human, etc… » Said Rabbi Yermia the son of El’azar: When the Holiness (Be it Blessed) created the first human, He cre ated him androgynous, for it says, «Male and female created He them.» Rabbi Samuel the son of Nahman said: When the Holiness (Be it blessed) created the first human, He made it two-faced, then he sawed it and made a back for this one and a back for that one. They objected to him: but it says, «He took one of his ribs [tsela’].» He answered [it means], «one of his sides,» similarly to that which is written, «And the side [tsela’] of the tabernacle» (Exod. 26:20)

The Rabbis envisioned the ideal human, the primordial being, as unsexed and undifferentiated, existing beyond the constraints of gender assignment. Following this interpretive line, Hebrew tradition as presented in the Zohar (a 13th-century text written in Castile but attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, a renowned teacher who lived in the late 1st century) explicitly refers to the ambiguity and androgyny of angels as a characteristic of privileged beings whose nature brings them closer to God. According to the Zohar, angels have «the form of a man, the form of a lion, the form of an ox, and the form of an eagle.» Furthermore, it states that «by ‘the form of a man,’ Scripture means the form of male and female together.» From this, it can be inferred that just as Zeus did, the Hebrew God Yahweh decided to deprive humanity of its original completeness or wholeness, in this case through its expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Thus, men and women are unable to participate in the state of bliss enjoyed by androgynous beings who revolve around God in the celestial spheres.

The Greco-Jewish philosopher and influential Torah commentator Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE – 40 CE) also attempted to formally reconcile the two accounts of the origin of humanity included in Genesis. Philo resolved the apparent contradiction between the two versions by interpreting them as two moments of the same creation process. Thus, the first human was a spiritual androgynous entity, that is, a being not yet tainted by matter, sex, and its division. The first human was both man and woman, and simultaneously, neither man nor woman. Later, according to Philo, God divided this entity into two sexed bodies. While this interpretation aligns with the rabbinic view, Philo of Alexandria’s writings significantly influenced the interpretations of Genesis by the so-called Fathers of the Catholic Church. In particular, Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254 CE) and Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395 CE) adopted the theory of the androgyny of the first human being. For Origen, the first creation would describe a human who is both incorporeal and sexually undifferentiated. The second creation would describe the infusion of the immaterial soul into the body, and with it, the initiation of sexual differentiation. Meanwhile, Gregory of Nyssa expanded this theory by understanding the immersion of the human soul in a sexed body as a direct consequence of the original sin.

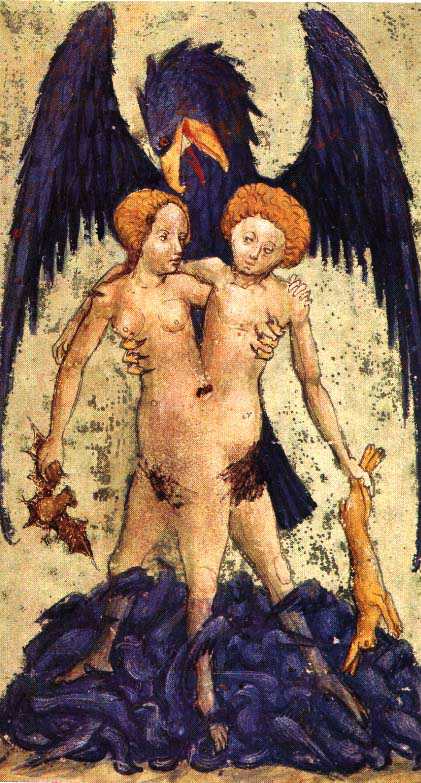

At the dawn of creation, Adam and Eve existed as an androgynous being, a sacred prototype that transcended physical boundaries and embodied divine purity. Regrettably, their transgression triggered a fundamental shift in their nature, activating anatomical and sexual differentiation and dividing the celestial entity into two genders: male and female. For Gregorio de Nisa, and later for medieval Catholic thinkers such as John Scotus Eriugena (c. 810-c. 877), sexual binarism would reflect the degraded or fallen condition of human beings. The degraded version of immortality would be our capacity to reproduce. What may seem paradoxical is that these Christian interpretations of Genesis consider that the highest state of humanity occurs in the absence of binary sexuality. Furthermore, sexual difference is not understood as an inherent part of human nature. God installed human sexual capacity as an aspect of their fallen reality. But that same divinity would restore humans to their original androgynous perfection.

Paradoxically, this Christian interpretation suggests that humanity existed in a state prior to sexual differentiation and will continue to exist in a state after it. During the Middle Ages, intense debates centered around the idea that humans would regain their androgynous and angelic state after the resurrection of the flesh at the end of times. For many theologians, the promise of resurrection was a promise of reconciliation of opposites, including the erasure of sexual distinctions. This interpretation was influenced by Saint Paul’s assertion in Galatians 3:28 that «there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female: for you are all one in Christ Jesus.» As John Scotus explained:

When Christ resurrected, he did not have a sex; however, to confirm the faith of his disciples, He appeared to them in a masculine form after his resurrection… But no believer should ever think or believe that He remained under the yoke of sex after the resurrection, for «in Christ Jesus there is neither male nor female,» but only the complete and true human being, that is, body, soul, and intellect without sex or finite form… The humanity of Christ, made one with divinity, is not contained in any place, does not move in any time, and is not circumscribed by any form or sex, for it has been exalted above all things… What Christ has achieved in a particular way, He will distribute in a general way to all of humanity on the day of our resurrection.

In the European Renaissance, alchemical texts began to draw parallels between the Risen Lord and the «hermaphrodite,» here understood as an agent of transformation capable of transmuting lead into gold and elevating fallen humanity into glorified humanity. In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the image of the «hermaphroditic Jesus» emerged, depicting a perfect balance of both masculine and feminine traits. This symbol not only challenged traditional binary gender categories but also suggested that embracing this balance could lead to physical and spiritual transformation for all of humanity.

In contemporary times, conservative Christians often appeal to the biblical story of Adam and Eve as evidence that God intended human beings to be strictly male or female. However, not all religious authorities of the past interpreted Genesis in this way. Despite those who use the Bible to justify their phobic aversion towards gender identities that challenge the binary of male/female, the truth is that the Western Christian imagination has often transcended this discreet dichotomy, particularly when imagining the critical coordinates of holy history and the highest degree of human perfection. Thus, while the figure of the androgynous came to represent the condition of humanity’s original purity, the Christian doctrine of resurrection, which postulated that all human beings would reclaim their bodies at the end of time, also turned to non-binary figuration to describe the type of bodily perfection required to experience the glory of eternity. Today’s fanatics would do well to recognize that the history of Christian thought does not always support their intolerance. Neither at the beginning nor at the end.

Una respuesta a “Androgynous Humanity: From before the beginning to beyond the end of times”

Compelling! Not to endorse contemporary androgyny but the plain understanding of Genesis, Christian eschatology, and history affirms this Edenic state of Adam and Eve and the future condition of the resurrected according to Christ’s words that “they will be neither married nor given in marriage but will be like the angels.”

Me gustaMe gusta